In the last video, we took a look at the early history of Laserdisc.

If you haven't seen that, you can find a link down below or up there.

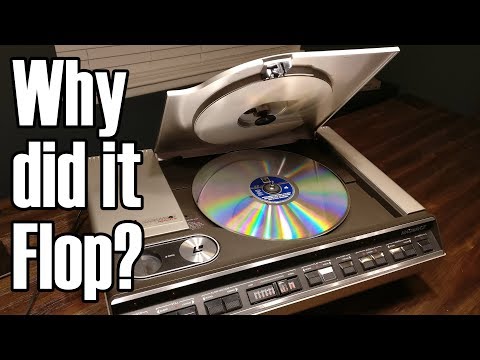

In short, Laserdisc was the first optical storage format, storing analog video on 12

inch reflective discs, and it was released at the end of the 1970's.

Featuring many of the noteworthy features of DVD, it may seem surprising that it didn't

become that popular.

It's market adoption barely reached 2 percent of videocassette recorder sales in North America,

and was even worse in Europe.

Its most successful market was in Asia, but even that wasn't fantastic.

Only 10% of Japanese households had a laserdisc player, and Japan was considered the healthiest market.

In this video, we'll find out why Laserdisc just sorta stayed in the background its entire life.

Let me begin by saying that the problem is more nuanced than simply, they cost too much.

Because initially, laserdiscs were far cheaper than videocassettes.

And it's also more nuanced than laserdisc's inability to record.

I began the previous video with

--A product with an unknown purpose that was both a few

years too late and way too far ahead of its time--

Those statements are interrelated, but let's start with the first one - an unknown purpose.

To understand that, you need to put yourself in the mindset of a consumer in the mid 1970s.

At that time, there were essentially two types of media you could purchase to consume at home.

Print media--that's books, newspapers, etc,--and music.

For nearly a century you could purchase music to play on a phonograph, and indeed this was

the first way we could listen to music at home.

(Static, buzzing, and tuning sounds)

(through the radio) Radio came later, providing a source

of free, nearly continuous programming.

But radio was a fleeting thing, and unless you had the patience to record a broadcast

with a tape recorder, go back and find the songs you actually want, dub them onto another

tape (which requires a second tape recorder), and then finally enjoy music uninterrupted,

you would just buy the album from your favorite artist on disc to play at home.

Indeed radio was pretty much how new artists were discovered and albums were sold.

Some of that still happens today, but we all seem to use streaming services or other, ehem,

means of getting our music on-demand.

Anyway, due to the short nature of musical radio content--generally only three minutes

or so for a song--the programming on a radio station wasn't usually organized beyond

an hour of such-and-such music.

Maybe you'd have a host for the afternoon drive, but the content being broadcast

would repeat multiple times during the day, as after all what's popular is popular.

This created little incentive for a radio listener to record the broadcast, which again

made the sale of music in record stores a logical, convenient thing.

This was especially true for less popular genres of music, where it would be rare to

hear it on the radio anyway.

For all these reasons, the consumer of 1975 was used to buying record albums to play at

home, and indeed wanted to.

Now if someone wanted to watch moving pictures, and I'm being deliberately vague here, they

had two options.

For long-form content, you would go to the the-a-ter to watch the newest releases.

Movies were obviously not a new thing in 1975, and the way you watched them had been the

same for many years.

A film was a thing you went to go see once, maybe twice, and wasn't something you would

expect to see at home over and over again.

Only the wealthy and eccentric would shell out the cash necessary to purchase a 16 millimeter

film projector and prints to go with it, with a true 35 millimeter projector and films being

the unobtanium of home entertainment.

Television was another story, though.

By 1975, more than 70 percent of households in the US had a color television.

But unlike music, which could be heard for free through the radio or as desired when

purchased on disc or tape, television was only a broadcast technology.

The viewer of a television had no control over what was being shown.

All you could control was what channel to tune into.

Movies were often broadcast on TV too, with a generous amount of commercial breaks peppered in,

but you still had no direct control over what to watch.

You were limited to what was offered.

But that was about to change.

By 1975, the public had been teased many times about a videodisc system which would revolutionize

the television experience.

RCA had been developing their videodisc since 1964, and Phillips had demonstrated an early

laserdisc prototype in 1969.

These companies along with others were trying to adapt the familiar concept of a record

player into a video player.

And they weren't shy about it.

You'll be able to buy video records, with movies, cooking classes, and all sorts of

new programming.

Imagine, television when you want it!

Keyword: Imagine.

While this certainly was a neat idea, it likely didn't resonate with many people.

To compel a consumer to purchase a videodisc player required you to convince them to buy

into a new kind of media.

It's not as simple as a new format, we're talking about something foreign.

It's an entirely different kind of content, all together!

(In unison) It's an entirely different kind of content.

No one had yet experienced what would come to be called home video.

It simply wasn't a thing.

The videodisc was a classic case of a solution in search of a problem.

Which brings us to the second issue.

It was too late.

Though the concept had been around for more than a decade, it took until 1978 for it to

be introduced, and it wasn't available nationwide for a couple of years.

But three years before Discovision came onto the scene, we got our hands on a different

technology which actually had a problem to solve.

Unlike radio programming, television shows took up a large chunk of your time, and were

far more immersive.

They were also scheduled, occurring on a known channel at a known time.

Generally, these shows were broadcast once a week, with over a dozen episodes produced

in a year.

The continuity, character development, and other serial aspects of the shows compelled

the viewer to watch every week, and missing your favorite television program was a severe

disappointment.

If only there were a device that could keep that from happening…

Enter the videocassette recorder.

In 1975, Sony released the Betamax system, and JVC followed with VHS a year later.

I'm not going to cover the format war between those two formats because I have already in

previous videos, but at this stage in the timeline, the format war was irrelevant.

And yes, there were earlier, unsuccessful systems, and I know about Video 2000, but

the existence of a VCR of any kind is what matters.

These machines promised to change how we watch TV.

If you were gone, you could tape your favorite shows using a built-in timer.

And if there were two shows you liked that were on at the same time, you could tape one

and watch the other.

The videocassette recorder had a problem to solve.

And it was perfect for the way television programming worked.

You knew when your show would be on thanks to the TV Guide, and there was an incentive

to not miss any episode of your favorite shows.

It sounds silly because TV is after all unimportant in the grand scheme of things, but the VCR

was seen by many people as a potential way to free up their schedule.

The act of recording a show to be watched later was called timeshifting, and that was

what sold VCRs.

If you had a VCR, it took the limitations of a format you were used to, that's television,

and removed them.

It solved a problem.

Now, here's where many discussions on the failure of Laserdisc get hung up, I'm looking

at you Simon Whistler.

When you look back to the beginning of the two formats, you'll see that they were meant

to be used completely differently.

Take a look at early advertisements for these machines, and you'll see that Laserdisc

wasn't really ever competing with VHS or Betamax.

This ad for this machine describes it as a turntable.

A VIDEO turntable.

And an excellent one at that, making pictures better than TV itself!

But you have to buy your video records, and the ad from 1981 shows that there are a whopping

120 to choose from!

Ah, that's so many!

Look at an ad for any VCR in the late 70s or early 80s, and you'll see it takes a

different approach.

This add for the RCA machine's 4-hour brother talks about television shows you want to put

on tape, and touts how easy it is to program it so you won't miss a thing.

You don't find anything about pre recorded tapes you can buy.

That's because the VCRs of this time period essentially predated modern home video.

The videocassette recorder wasn't being marketed as a device to play a pre-recorded tape.

Content distribution of that kind wasn't a thing yet, in large part due to the high

cost of producing video cassettes.

That's right, here's another thing in the saga on Laserdisc that gets overlooked.

The idea behind videodiscs in general was that they could be mass-produced quickly and cheaply.

Since they are stamped like vinyl records, with RCA's ill-fated CED system literally

being a vinyl record, the discs could be made pretty easily.

From an ad linked in the description, the original cost of Discovision titles was intended

to be $5.95 or $9.95 for half-hour and hour long titles, respectively, with new feature

films priced at $15.95.

Adjusted for inflation that may seem pricey, but considering the price chart from Popular

Mechanics shows the cheapest one-hour BLANK VHS tape

--that's blank, with nothing on it--

going for $16.95, you get a sense of why the disc was considered better for content

distribution.

The tape used in videocassettes was a brand new, very specialized fine particle tape.

It was expensive to produce well over 200 meters of the stuff for each cassette.

And to mass produce pre-recorded video tapes in a meaningful quantity would require hundreds

of separate videocassette recorders, each spending the entire runtime of the program

being recorded to actually produce a duplicate tape.

One machine could make dozens of laserdiscs per hour, whereas one video tape duplicator

would take more than an hour per tape.

And the laserdisc players were cheaper, too!

That same chart shows the cheapest VCR costing $995.

This magnavision player started at $699.

And it doesn't seem as though that cost was subsidized by potential profit from selling

discs, as Philips/Magnavox and Discovision were separate entities.

So then, say you're a consumer in 1980 deciding between these two machines.

The Magnavision is touted as having stereo sound and an incredible picture, and there

are exciting interactive possibilities to go along with it.

But there's not a lot of content you can watch.

You'd save a few hundred dollars buying it, but once you've purchased 20 or so movies,

you'll have spent all that anyway.

The long-term cost of ownership doesn't really add up.

The VCR, though, is a somewhat mature technology.

You know people who use them, and they love them!

And while this machine is more expensive, and so are the tapes, you can't see yourself

needing more than one tape.

You still aren't sure you need to save a TV program after you've seen it, after all

that's not been possible before, so after you've watched the shows you missed that

week, you can re-use the same tape.

Who cares if it's more expensive so long as it's reusable?

If you buy the Magnavision machine, how often will you really use it?

You'd have to be buying a disc every day to get serious use out of it, and that'll

get expensive fast.

Sure the frame-by-frame and slow-motion features are a neat gimmick, and the possibilitiy

of an art encyclopedia is kinda cool, but that will only occupy a few hours of time.

You're pretty sure you'd get bored with it, and need to buy another disc.

You know you'd use the VCR at least once a week; M*A*S*H and Mork and Mindy are on

at the same time, and you've always wanted to watch both.

Plus, you can never stay up late enough to watch Johnny Carson.

Maybe you'll use it daily.

Sure it's kinda ugly and clunky, but who cares if it does its job?

Do you really need the better picture of this machine?

You only have a 19 inch television at home, who knows if you could even see the difference?

And who really needs stereo sound for TV?

Nothing on TV's in stereo anyway.

And I doubt you'll rearrange the living room just to have this machine play through

your hi-fi.

See the problem?

A Laserdisc player was a technological marvel with some neat tricks up its sleeves, but

its lengthy development time caused it to be released after videocassette recorders.

If Laserdisc had been available, say, in 1970, I don't think it would have struggled like it did.

Without the existence of a videocassette recorder, the idea of buying content to watch on your

schedule might be more appealing.

After all, you've been doing the same thing with music for decades, and there would be

nothing else to allow you that sort of flexibility on your TV.

But with the VCR already on the market, suddenly the Laserdisc has to convince buyers to forgo

timeshifting capabilities for cheap-to-own movies.

Which again, was an odd proposition to many consumers of the time, having never been able

to own a movie before.

The idea of owning movies was also a foreign idea to movie studios.

They had never before needed to think about how to sell their content for mass home consumption.

Laserdisc was trying to start an entirely new market category: that of home video.

With MCA backing the Discovision format, their catalogue of content could easily be licensed.

But Discovision would face challenges when trying to license other content.

Movie studios were understandably reluctant to sell their catalogues of movies to a company

like Discovision.

Before home video, it wasn't uncommon for older movies to be released in theaters again.

The movie studios were used to charging essentially per-view, and a home video solution goes entirely

against that.

The issue of licensing was further complicated in the disc realm by competing standards and

confusing branding.

With the development of their CED system, RCA was hard at work convincing movie studios

that they should license their content to RCA.

This might have limited the content available to Discovision if any exclusivity clauses

were added to the contracts signed.

It was also frustrating to consumers, as they didn't know which disc system would be better

supported with content down the road.

And even among Laserdisc players, Magnavox continued to refer to this as Magnavision,

even though the discs you could buy were called Discovision

and the format had been christened Laservision

by this time.

This fear and confusion probably kept a good number of videodisc players on store shelves.

Thus began a chicken-and-egg problem.

Buying a laserdisc player in the early years meant buying into a system with limited content.

This kept sales low.

Which meant there weren't a lot of people with players.

Which meant the movie studios couldn't make much money selling discs.

Which meant there wasn't much content, which kept the sales of players low, and the cycle continued.

But videocassette recorders didn't have that problem in the slightest.

Going back to our ad, you'll remember that pre-recorded content isn't mentioned at all.

That's because, this wasn't their primary purpose.

Time-shifting was what you did with a VCR.

It didn't have anything to do with buying a movie to watch over and over again.

Who would want that?

But plenty of people would want to record their TV shows while they weren't at home.

That was an idea you could get behind.

As more and more people purchased a VCR, suddenly there was a large installed base of devices

that could play a pre-recorded tape.

And now there was a place for home video.

Tapes needed to get cheaper to manufacture, and duplication facilities needed to mature.

But once those things happened, it became easier for movie studios to get behind the

idea of selling their movies for watching at home.

Especially their older and classic films which wouldn't make too much money with a new

screening, but might turn a decent profit on home video.

Now that home video was an established business, buying a laserdisc player made even less sense

to the average consumer.

What was the point of buying another machine when I already have a VCR, now that the big

movie studios are all releasing their movies on VHS and Beta?

And to be honest, Laserdisc was an inconvenient format.

Pretty much every single movie is longer than an hour, so you're guaranteed to have to

flip the disc over.

And if you push into 2 hours, you'll need another disc.

VHS and Beta were largely immune to this, though very long titles would push onto a

second cassette.

And then there was the rental market.

Videocassettes may have cost more to make than laserdiscs, but many people weren't

buying them, they were renting them.

A rental store owner would make the cost of the tape back many times over, so the high

cost of the purchase wasn't that impactful.

And cassettes made more sense for rental, as their design is inherently less fragile.

The tape does wear out over time which Laserdisc was (at least they thought) immune to

--it wasn't!--

but any surface scratches on the surface of a Laserdisc would immediately harm

the image quality.

And the smaller, chunky nature of a videocassette was easier to transport than the flat, large

size of the laserdisc.

As years passed, the videocassette received the benefits of economies of scale much more

than Laserdisc did.

Though it should be noted that the price disparity between laserdisc and tapes continued for

some time.

There's a clip on YouTube of Siskel and Ebert and the Movies, and in it they discuss

how the film Running on Empty, released in theaters in 1988--

"that came out at 89.95 on tape, but 24.98 on disc"

--But they also noted that at this time, movie studios were

beginning to sell cheap tapes.

Paramount had been releasing some films on tape for $14.95 with some bargain tapes going for $9.95.

The trend of tapes continuing to get cheaper would go on, and Laserdiscs wouldn't get

to join in on that.

At this point, it might seem that Laserdisc would be doomed.

Being beaten to market by a device which could record really hurt its chances, and once the

movie studios had started offering their content on VHS and Beta, buying a second device just

for watching movies didn't make tons of sense.

But Laserdisc didn't die.

It clinged to life until 2000, co-existing with DVD for 4 years.

It was the collectors market, and to a lesser extent the education market, that saved them

from a complete death.

Those who bought Laserdisc from the mid 1980's onward largely did so for reasons of quality

and exclusive content.

In the next video, we'll look at how Laserdisc evolved over the years into the pinnacle of

home entertainment, and we'll also look more closely at the features--and follies--of

the format itself.

Thanks for watching.

If this is your first time coming across the channel, please consider subscribing.

This channel is made possible by supporters on Patreon.

Patrons of the channel are what keeps these videos coming, and each of you deserves thanks.

If you're interested in supporting the channel as well, please check out my Patreon page

through the link on your screen, or down below in the description.

Thanks for your consideration, and I'll see you next time!

...ability to record.

I began the previous video with (in a quick, snarky, nasal voice) A product with an unknown

purpose that was both a few years too late and way too far ahead of its time

For more infomation >> El gordo cabrón - Duration: 2:52.

For more infomation >> El gordo cabrón - Duration: 2:52.  For more infomation >> Alec Baldwin abandona Twitter por el escándalo Harvey Weinstein - Duration: 4:54.

For more infomation >> Alec Baldwin abandona Twitter por el escándalo Harvey Weinstein - Duration: 4:54.  For more infomation >> A importância do pequeno empreendedor na formação do Brasil - Duration: 2:01.

For more infomation >> A importância do pequeno empreendedor na formação do Brasil - Duration: 2:01.  For more infomation >> 표범 니달리 스킨 추천 인게임|K-News - Duration: 1:55.

For more infomation >> 표범 니달리 스킨 추천 인게임|K-News - Duration: 1:55.  For more infomation >> 9 exercices pour brûler la graisse abdominale en 14 jours seulement - Duration: 7:01.

For more infomation >> 9 exercices pour brûler la graisse abdominale en 14 jours seulement - Duration: 7:01.  For more infomation >> 어느 휠 회사의 실패한 홍보 이미지[ 자동차 세계 24_7] - Duration: 4:13.

For more infomation >> 어느 휠 회사의 실패한 홍보 이미지[ 자동차 세계 24_7] - Duration: 4:13.  For more infomation >> 베이징현대 승부수..'사드 난국' 속 충칭공장 본격 가동[ 자동차 세계 24_7] - Duration: 4:36.

For more infomation >> 베이징현대 승부수..'사드 난국' 속 충칭공장 본격 가동[ 자동차 세계 24_7] - Duration: 4:36.  For more infomation >> DS, 내년에 소형 전기 SUV 선보인다[ 자동차 세계 24_7] - Duration: 2:29.

For more infomation >> DS, 내년에 소형 전기 SUV 선보인다[ 자동차 세계 24_7] - Duration: 2:29.  For more infomation >> Real Food Vs. Gummy Fount...

For more infomation >> Real Food Vs. Gummy Fount... For more infomation >> Forsyth County 4-H Plant Sale - Duration: 2:37.

For more infomation >> Forsyth County 4-H Plant Sale - Duration: 2:37.

For more infomation >> Medytacja Pisma Świętego - Czy Bóg może mnie uzdrowić? [#Mk 1,29-39] - dla niesłyszących (j. migowy) - Duration: 1:08:38.

For more infomation >> Medytacja Pisma Świętego - Czy Bóg może mnie uzdrowić? [#Mk 1,29-39] - dla niesłyszących (j. migowy) - Duration: 1:08:38.  For more infomation >> ТОП-10 ЛУЧШИХ ВЫПУСКНИКОВ МАНЧЕСТЕР ЮНАЙТЕД [АКАДЕМИЧЕСКАЯ ДЕСЯТКА] - Duration: 14:17.

For more infomation >> ТОП-10 ЛУЧШИХ ВЫПУСКНИКОВ МАНЧЕСТЕР ЮНАЙТЕД [АКАДЕМИЧЕСКАЯ ДЕСЯТКА] - Duration: 14:17.  For more infomation >> 9 La brochette de à vomir - Duration: 21:43.

For more infomation >> 9 La brochette de à vomir - Duration: 21:43.  For more infomation >> video fortnite #1 - Duration: 12:43.

For more infomation >> video fortnite #1 - Duration: 12:43.

No comments:

Post a Comment