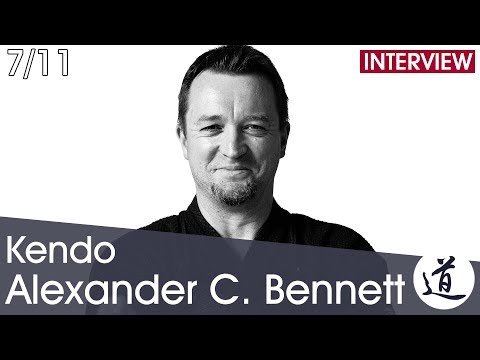

Alexander C. Bennett has two PHDs in Human Studies and Sciences

from the University of Canterbury and Kyoto University.

He holds the ranks of 7th dan Kyoshi in Kendo, 5th dan in Iaido and Naginata,

3rd Dan in Jukendo and Tankendo.

He is professor at Kansai University of both Kendo and Japanese Culture and History,

vice-president of the International Naginata Federation, member of the international committee of the

All Japan Kendo Federation, director at the Japanese Academy of Budo, cofounder of the

Kendo World Magazine, and author of several books in English and Japanese.

I think it's really healthy to always be skeptical and, you know,

not in a negative way, but just to question everything and always ask, you know: "Why?"

"Why am I doing this?"

"Why am I doing this?"

"What am I after, here?"

Because there are times in Japan which is like...

It is like you say. They... You...

There's like, you know...

At work there's a lot of pressure to do things and you push yourself.

But the problem is, it's not always clear what the purpose is.

There's a lot of wasted effort in Japan, I believe.

And I think that one of the keys to my survival so far

is that I've been able to distance myself from the bullshit when I smell it.

There was a time when I couldn't do that, you know?

And there's also other things, you know ?

The longer you live here, you look back on what you used to be like in Japan,

and then there's words that I use like

"Geekas Nipponica" and "Japan droid" and things like that.

It's like, when you first come over here: "Oh Japan, so cool!"

"Everything's so cool about Japan!"

"Even the bad stuff is really cool!"

And then you get other people who, sort of, figure that: "Ah!"

"Because I'm in Japan, I must become Japanese!"

And you do everything you can to act, and behave, and speak, and be more Japanese than the Japanese.

And when people say to you: "Oh nihonjin, yori nihonjin rashii daro" (You're more Japanese than the Japanese)

and you're so "Uh!".

It's like a, you know, an affirmation that you have successfully assimilated

and you're one of everybody else in Japan, and this is great.

It's like...

I know this because I've been there, right?

And when I was younger it's like :"Oh well, I'm in Japan, I've got to try and be Japanese!".

After a while you realize that: "I'm not Japanese for God's sake!"

It was one thing that sort of woke me up to that.

It was a very timely, another very timely piece of advice.

I was hell-bent on trying to be as Japanese as possible

because that's what I thought you had to do to be accepted, you know, in Budo and…

And in Japan in general.

And when you start doing that, that means that, essentially, you're negating your true self

and your own, sort of, cultural background, and, you know, your moral outlook and...

You know there's always going to be conflict with certain things and so:

"Well, I'm in Japan so I've got to do it this way!" it's like... It can be very stressful.

It can be very stressful.

And I remember one day in Shubukan, actually, with Mitamura-sensei.

She's a legendary Naginata teacher.

And she was in her mid to late 70s at the time, and she said to me:

"Wow Alex, I can see that you're trying so hard."

"You know, you're doing your best to behave like a Japanese,

speak like a Japanese and you come to training and you're very diligent,

but just remember that you don't have to copy the bad things in Japan.

There must be some good things in New Zealand too, right?"

A very simple statement and it's like: "Yeah."

"What the hell am I doing?"

"I'll just be Alex Bennett making the best, you know, out of both worlds that I'm lucky enough to have, you know,

a part of me."

You know, talking about it now it's obviously really simple, right?

But when you're young and you're trying to make your way in Japan, you don't see it like that.

You miss that. And such...

Little bits of, you know, advice like that, that I've received, would, sort of, wake me up a little bit.

That managed, well... It has enabled me to just, when I need to, keep my distance.

Choose your battles, as it were.

Because once you lose sight of that, then it's a losing battle.

And it's really sad, you know?

All the time people become...

They come here with the best intentions to learn Budo and, you know, all the stuff

and then before long they…

They peter out.

They lose that enthusiasm, they lose that flame.

They're…

Everything becomes overshadowed by negativity, the stuff that just doesn't make sense:

the politics and, you know, all that sort of crap.

And you've got to remember, so: "Well what do I like to do?"

"I like going to the dojo and training, getting it on and..."

"Bam!"

"Sweating and screaming and yelling."

And then thinking about, you know, all the ways, that what I'm doing in the dojo,

philosophically speaking, can be useful in my daily life as well.

It's really easy to lose sight of what's important, and living in Japan it's a...

You know, people often have these ideas of the Japanese way of doing things is so brilliant and efficient,

but it's not.

You know, it's like anywhere.

Like everywhere in the world, you know, you have your good points and your bad points.

But in Japan it's...

I don't know.

I guess the biggest difference between coming from New Zealand and Japan is in New Zealand,

and this is obviously a total generalization, in New Zealand we would say:

"Oh nobody's done this before. Okay let's try it!"

But in Japan it's: "Nobody's done this before."

"Who's going to take this... We can't do this! We can't do this because..."

"What if it goes wrong? Who is going to take responsibility?" you know?

And that's the biggest conflict that I have in my work, when you try and do new things.

They just won't let you do it.

You're constantly banging your head up against a brick wall.

But doing Budo, training individually, that's exactly what you've got to do.

You're always looking for ways to do something a little bit differently, to improve,

just to develop your art.

And that's...

You know, the fact that I can live in Japan, it was because of Budo that I came to Japan and was living in Japan.

Now it's because of Budo that I can stay in Japan.

Do you, sort of, know...

Do you see what I mean?

It gives me that freedom now.

You know, there's always stuff going on, and it's always, you know, various things that happen in the dojo

but it's like, well, you know: "That's not important to me."

"This is important for me."

"This is my space."

"I'm creating my art."

And, you know: "If you don't want to help with that, bugger off."

Yeah...

In the next episode, we're starting the second part of the series by talking about the origins of Japanese Budo.

First topic is the creation of the Kodokan Judo by Jigoro Kano.

Modern Budo really, sort of, starts with Judo and Kano Jigoro.

He used to get bullied.

Teach these bullies a lesson.

If you think of it now, you think: "Wow it's ridiculous!" because he was only 22.

Part of the education system was modeled on the Western.

If you try to introduce martial arts into the school curriculum, which ones do you introduce?

Stay tuned.

You'll learn a lot about the history of Budo in the next episodes.

For more infomation >> Les signes précurseurs du cancer de sein que les femmes ne prennent pas au sérieux - Duration: 6:23.

For more infomation >> Les signes précurseurs du cancer de sein que les femmes ne prennent pas au sérieux - Duration: 6:23.  For more infomation >> f**k it therapie faisons le point ....rien à foutre rien à battre - Duration: 10:28.

For more infomation >> f**k it therapie faisons le point ....rien à foutre rien à battre - Duration: 10:28.  For more infomation >> 【驚愕】<小林麻耶>市川海老蔵宅に同居で再婚状態?お泊まり報道? - Duration: 5:41.

For more infomation >> 【驚愕】<小林麻耶>市川海老蔵宅に同居で再婚状態?お泊まり報道? - Duration: 5:41.  For more infomation >> Issawa Simohamed Belmehdi à Golf Palace d'agadir - Duration: 1:55.

For more infomation >> Issawa Simohamed Belmehdi à Golf Palace d'agadir - Duration: 1:55.

For more infomation >> EasyJet Passenger Holding Baby PUNCHED By Nice Airport Worker!!! - Duration: 3:01.

For more infomation >> EasyJet Passenger Holding Baby PUNCHED By Nice Airport Worker!!! - Duration: 3:01.  For more infomation >> Alice & Hatter | The Night We Met (Random Picker #01) - Duration: 2:00.

For more infomation >> Alice & Hatter | The Night We Met (Random Picker #01) - Duration: 2:00.

No comments:

Post a Comment